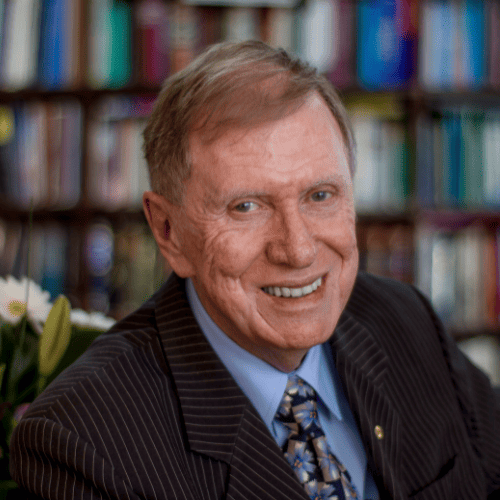

The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG*

The United Nations Organisation was established in 1945, in the aftermath of the conclusion of the Second World War. The United Nations was created by the adoption, in San Francisco in 1945 of the UN Charter. That instrument specifically envisaged the attainment of peace and security; universal human rights; the right of self-determination of peoples; decolonisation and equality.

Initially, it was proposed that in the Charter, there would be included an international Bill of Rights. However, disputes arose as to the content of those rights. It was therefore decided that the drafting of such provisions would be assigned to a committee of the United Nations. That committee was to be chaired by Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt, the widow of the former US wartime leader, Franklin Roosevelt. She performed a great service to humanity by securing the agreement of nation states to a Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). She worked with a secretariat that was provided to her by the General Assembly. The head of that secretariat was Mr [later Professor] John Humphrey of Canada. His proposals eventually came before the General Assembly.

Because the United Nations building in Manhattan had not been completed, on the day of the adoption of the UDHR (10 December 1948) the General Assembly was meeting in Paris, France. This was the third session of the General Assembly since it was established in 1945. The President of the General Assembly was an Australian, Dr H.V. Evatt KC. He had been a Justice of the High Court of Australia (1930-40). However, he resigned that post when the war broke out. He served in the Curtin and Chifley Labor Governments. He was highly influential in relation to the adoption of the Charter and of the UDHR. Evatt was a brilliant scholar and judge. He attended the same school as I did decades later (Fort Street Boys’ High School in Sydney). I was to meet him later still when he was old, and I was young. But in 1948, he was serving in the United Nations in his capacity as Australia’s Foreign Minister. As the third President of the General Assembly, it was Evatt’s privilege to preside in the adoption of the UDHR. When he banged his gavel to signify adoption, he declared that the UDHR would be a “Magna Carta for all mankind”. So it has proved.

On 10 December 2023, in the midst of gloomy days, the world will celebrate the important achievement of the UDHR. It has been hugely influential although it is not a binding treaty. Its 30 articles have been acknowledged as expressing those civil, political, social, economic and cultural rights that belong to human beings simply because they are human. In the debate before Evatt pronounced the endorsement of the UDHR, a number of countries (such as Saudi Arabia and Apartheid South Africa) abstained. But no countries recorded their vote against the UDHR. On 10 December 2023, the world will celebrate the 75th anniversary of the adoption of the UDHR. Its achievement was a mighty accomplishment for the fledging United Nations and for the course of human life and liberty.

In this essay I remember my own tiny connections with the three personalities that were so important in the preparation of this most important universal declaration. The UDHR is the most translated and publicised international instrument in existence. I want to describe how I became aware of it.

First, let me mention Eleanor Roosevelt herself. As wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, she played an unusually active role in his public life. She was highly talented and a supporter of women’s rights and the rights of African Americans, long before those causes became common. She was even ahead of her husband in these and other respects. She wrote a regular newspaper column. This was read across America and the world, during the Depression and the later War years. Eleanor Roosevelt was highly intelligent and articulate. She was also greatly loved, but as well, hated and mistrusted in some circles hostile to her new ideas. Because of President Roosevelt’s physical disability (he was wheelchair bound resulting from an exposure to poliomyelitis as a young man), Eleanor Roosevelt was called upon to step in for her husband sometimes. One such occasion was when she made an island-hopping journey by plane to Australia, in the midst of the Pacific War with Japan that included the United States and Australia as Allies.

This journey was designed to raise the morale of American soldiers in the deadly theatre of war on Australia’s doorstep in 1944. At the end of this journey, the President sent Eleanor to Australia to acknowledge and reaffirm the alliance with the United States and the common sacrifices shared by both during the War. To respond to those sacrifices, a large modern hospital was erected in Concord West in the inner Sydney suburbs. The United States Government substantially funded its construction. During her visit to Australia, Eleanor Roosevelt was designated to perform the opening of the large institution built on the Parramatta River in Sydney, Australia’s largest city.

As it happened, my parents had established our family home in the suburb of Concord. My first school was the North Strathfield Infants’ School in that suburb. On a day I remember, the students of this public primary school were summoned to the footpath in front of the school. At the time many large trucks, with Red Cross insignia on them, regularly passed by our school. On this occasion, we were told that a great lady was going to pass by. We were given flags to wave and to welcome her to Australia and to thank her and the American servicemen and women for the part they were playing in achieving a victory. When Elanor Roosevelt drove by my school, I swear that I caught the eyes of this great lady. Our eyes locked, in common cause. I became a grateful follower of the UDHR which Mrs Roosevelt had delivered later to the General Assembly of the United Nations.

In the mid-1980s I was serving as President of the NSW Court of Appeal. Doubtless because of that appointment, I was elected to be a Commissioner of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) for Australia. This is a body of leading lawyers and human rights experts set up in Geneva after the War to follow up and protect the achievement of the principles of the UN Charter and of the UDHR. At the time of my election, the Canadian Commissioner was Professor John Humphrey, by this time back at his post at McGill University. I spent a lot of time in his company. Inevitably, we often talked of the UDHR in 1948.

John Humphrey had lost an arm in a youthful accident. He was a brilliant man but occasionally irascible. I talked to him about his experience with Eleanor Roosevelt and the committee drafting the UDHR. His eyes lit up as he remembered the travel he made on the bus to work in Lake Success, New York. This was where the UN secretariat was back in 1947-48. The move to the foot of 42nd Street Manhattan came later. The Secretary-General of the UN at the time was Trygve Lie from Norway. John Humphrey told me about the political and administrative arrangements in those days. On the bus to work, when an idea for the UDHR popped into his head, he would make a note to himself. Later those notes became the basis for his suggested provisions for the UDHR. In such humble and seemingly accidental ways, mighty achievements are sometimes accomplished.

Years later, in the United Nations building in Manhattan, I saw on a wall in the Human Rights office a photograph of a postage stamp issued by the Government of Canada to celebrate the life of John Humphrey. In the stamp was portrayed his beautiful cursive handwriting expressing the opening provisions of the first article of the UDHR. It said: “All human beings are free and equal in dignity and rights.” I am a direct link between this generation and the heroes of the age in which the UDHR was born.

The third hero in this trinity is Herbert Vere Evatt. He never attained his dearest wish to be elected Prime Minister of Australia. However, in every other way, he succeeded greatly. He was not only appointed the Federal Minister for External Affairs, but he was also Federal Attorney General and a member of the Curtin War Cabinet for Australia. He became the Leader of the Opposition on the death of Prime Minister Chifley in 1951. In the early days of the Menzies Government, he led the opposition to the validity of the Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 (Commonwealth). That law was enacted in 1950 to ban the Australian Communist Party and to impose civil penalties on communists. Evatt personally argued the invalidity of that Act before his former colleagues in the High Court of Australia. To the astonishment of Prime Minister Robert G. Menzies, he succeeded in the High Court. It is one of the greatest decisions in the history of the High Court. It upholds limitations on the power of government to intrude into the beliefs of citizens, including political beliefs. When Mr Menzies immediately proposed a referendum to amend the Australian Constitution to overcome the High Court decision, Evatt campaigned vigorously against the change to the Constitution. In the result, Menzies did not secure the “double majority” required by s128 of the Australian Constitution: a majority of all the electors in the Commonwealth and as a majority in a majority of the States. It was an important decision for liberty in our country.

Because, prior to 1950-51, my grandmother had remarried and her new husband was the national treasurer of the Australian Communist Party, the story of Evatt’s defeat of the legislation was much discussed in our home. I met Evatt at a couple of school functions in the 1950s. I also met him later when he was Chief Justice of New South Wales in the 1960s. By then he was a pale shadow of the hero of earlier days. However, when I looked at him, I always saw him using the gavel as third President of the General Assembly of the United Nations.

In 1949, the year the UDHR was adopted in Paris, I was attending Summer Hill public school in New South Wales. Our new teacher was Mr Keith Gorringe. He had been a soldier in the Australian Defence Force in the Second World War. He taught his students the importance of knowledge about, and compliance with, the UDHR. In his class in suburban Sydney, we received from the United Nations, a copy of the UDHR which I kept for many years. They were sent from New York on the initiative of the leader of the Australian Delegation to the United Nations, H.V. Evatt. Mr Gorringe taught us about the contents of the document. Evatt knew the importance of education for the observance of universal human rights. He was wise in selecting Australian schools to receive copies. I was fortunate to have a teacher with the recent experience and motivation to insist on that importance. He taught its relevance to us. The daily newspapers were, for the first time, showing photographs of the mushroom clouds that gathered over the test sites of the nuclear weapons, then ominously, being developed and tested. As our teacher taught us and is still true: unless humanity can learn about and observe the lessons of the UDHR, the prospects of the survival of our species and of our habitat in this lovely watery planet looks problematic. So that is the importance of the UDHR of 1948. Unless we learn its lessons our survival on planet earth will be doubtful and full of danger.

When Evatt died in 1963, he instructed that the only office of the many great offices he had held that should appear on his tombstone was “Third President of the General Assembly of the United Nations”. Exercising that office, he brought into force the UN UDHR. His career illustrates the proposition that we all have challenges at different stages in our lives. When it matters, we must all stand up for fundamental principles. We must celebrate UDHR 75 years after its adoption. This small note has been designed to illustrate the human dimension of that document and its importance for Australia of the work of three heroes of universal human rights: Eleanor Roosevelt (USA), negotiator John Humphrey (Canada), drafter; and Herbert V. Evatt (Australia), implementor and defender.

* Australian Human Rights Medal 1991; President of the International Commission of Jurists 1995-8; Laureate of the UNESCO Prize in Human Rights Education 1998; Co-chair of the International Bar Association Human Rights Institute 2019-22.

DTP acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we work, the Bedegal people of the Eora Nation. We recognise their lands were never ceded, and we acknowledge their struggles for recognition and rights and pay our respects to the Elders – past, present – and the youth who are working towards a brighter tomorrow. This continent always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be aware that this website contains images or names of people who have passed away.

DTP acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we work, the Bedegal people of the Eora Nation. We recognise their lands were never ceded, and we acknowledge their struggles for recognition and rights and pay our respects to the Elders – past, present – and the youth who are working towards a brighter tomorrow. This continent always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be aware that this website contains images or names of people who have passed away.

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Disclaimer | Policies

© 2022 Diplomacy Training Program | ABN 31 003 925 148 | Web Design by Studio Clvr